Water Warrior

By Bud Elliott

[Editor’s Note: Since this article was published in April of 2015, Jose Ramirez has won five more bouts. His record is now 18-0-0 with 13 knockouts. His next fight will be in December at the Save Mart Center]

Late one sweltering summer afternoon not that many years ago, some neighborhood kids walked home after boxing practice in the dusty, south Valley town of Avenal. An older and bigger kid, maybe 10 or 11, followed close behind, taunting little Jose. Schoolboy smack. Nothing serious.

Suddenly, the skinny 8-year old stopped, turned and delivered an uppercut to the older boy’s solar plexus. Silently, he turned back to the group and continued homeward, leaving the bully bent over on the sidewalk in tears. Jose’s sister, Karla, recalls the event vividly because it so clearly illustrates the character of Jose Carlos Ramirez then and now, “‘He’ll be okay,’ he said, at the time, “He’ll be okay.'”

The next day at school, Jose apologized to the older kid and extracted a truce that was never broken.

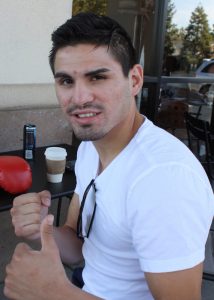

Now at 22, there is no brashness, no bravado nor swagger about the young man who remains undefeated in his professional boxing career at 13-0 and holds the NABF Junior Welterweight title.

He is disarmingly mild-mannered and humble in his dealings with the world outside the ring and genuinely unaffected by the riches, which have already come his way. Rick Mirigian, his agent-manager, sums up his character in just six words: “He speaks softly. Punches very hard.”

Heart of a Lion

Jose Ramirez fought six times in 2014. Six times he won – five times by knockout. He dispatched Javier Perez in just two-and-a-half minutes. He knocked out Boyd Henley in 50-seconds. Yes, he punches very hard, each blow recorded and evaluated in a sport obsessed with numbers and statistics. Yet to this day, the experts and analysts, promoters and predictors have not figured a way to hang a ranking on heart – whatever it is inside that compels a young man (and frequently now, women) to enter a square space enclosed by ropes twenty-feet on each side for the sole purpose of inflicting physical damage on an opponent, while defending against an equal measure of painful, violent, often injurious blows.

Norman Mailer once said of amateur boxer Ernest Hemingway, “There are two kinds of brave men. Those who are brave by the grace of nature, and those who are brave by an act of will.” Mailer assigned the second attribute to Hemingway. A close observer would not be wrong to conclude that Welterweight boxer Jose Carlos Ramirez of Avenal possesses both.

Near the end of every Jose Ramirez boxing match the pace quickens. Something shifts in the opponent’s resolve. Like the 22-year old Muhammed Ali in 1964 – his first title fight. He so bewildered Heavyweight Champion Sonny Liston with his flash and speed and style that Liston simply “quit on his stool” and didn’t come out for the seventh round of a twelve round fight.

“Yes, I see that often,” says Ramirez, “I see it in their body language, the look on their face, or in their eyes, and I know that it’s time.”

December 13, 2014 at the plush Chelsea Room inside The Cosmopolitan Las Vegas. HBO cameras were there. A Junior Welterweight bout against Antonio Arellano of San Ysidro. Left-right-left-left. The sixth and final round. Ramirez doesn’t play any musical instruments, but he used his two 8-ounce gloves like a couple of drumsticks. Right-left-right-right. The paradiddle, every drummer knows it. A lightening left hook to the ribcage drew a gasp from Arrellano and sends him into a fog bank from which he will not emerge. Just like trainer Freddie Roach taught Ramirez, and his godfather, Armando Mancinas before that. JAB–HOOK–JAB–JAB. Faster now!

“He’s a devastating body puncher,” Mirigian says, “always has been.” (Word is, he once hurt welterweight champion Manny Paquiao with a left to the ribs during a sparring session and the champ had to call it off.)

Twenty-six seconds later, dazed and confused, Arellano walked into a staggering Ramirez flurry ending with a monumental overhand left hook to the temple. Referee Pat Russell stopped the music with ten seconds remaining. Fog turned to cold sleep. Victory number thirteen. Sweet music.

“To win you gotta hit and not get hit,” says Ramirez, who has always maintained that his defense is better than his offense. “I’m glad this fight went six rounds. I made some mistakes. He got to me a couple of times. It gives my trainers more things for me to work on.”

Wiry and rambunctious and bursting with energy, Jose Ramirez has always been in motion. His mother, Juanita, finally put her foot down in the summer of 2000 when 8-year old Jose and younger brother, Luis, were caught (again) jumping from the roof of the house –just for fun. Basta! Enough, already! Mom directed dad, Carlos Ramirez, to find something for all four kids to do during summer vacation. Pronto. So, he marched Luis, Jose, Karla, and Lalo down the block to the newly-opened Police Athletic League’s Kings Boxing Club.

All four kids learned to box, but only Jose fell in love. “He was a natural,” Karla says. “He loved it and you could tell. He actually quit once but went back right away. He’d come home at night all excited about something Armando (Mancinas) had taught him. He loved to train. He loved to learn. He was a good student and a good athlete to begin with – soccer, basketball, track, cross country, you name it. But boxing? That was his joy, right from the start.”

Everybody who grows up in the town of Avenal learns hard truths about brutally difficult work in the fields and orchards and vineyards and packing sheds. Drugs and gangs, rap sheets and trouble start at an early age. Yet, when Mirigian entered the Ramirez family home for the first time he found something completely unexpected. “Jose was soft spoken; he was deeply spiritual; he had a family setting and bonding, which to me was a support cast that was unbelievable. I asked him, why do you box? Without the slightest hesitation he said, ‘I box to someday take care of my family. I fight for them first.'”

“He’s broken every amateur record of great boxing names – Floyd Mayweather, Jr., Oscar De La Hoya, Shane Moseley.” Mirigian says. “At this point in his career, Jose Ramirez has exceeded the records, including amateur championships, of the four biggest-earning boxers in history, with a combined pay-per-view gross of $3-to-$4 billion dollars.”

Ramirez won a spot on the USA Olympic Team in 2012 by emerging from a field 200 boxers in the first round of qualifying in Colorado Springs, and an unconventional second round of eliminations in Alabama.

“At one point he had to make weight and then fight once a day for seven straight days,” says Mirigian. “Kids don’t fight like that. Nobody does.”

But then, nobody trains like Jose Ramirez, either. In 2011, the year leading up to the Olympic trials, Jose pursued a punishing schedule of early morning drives from Avenal to Fresno to attend Fresno State. He carried a full load of freshman business classes, including calculus. Home again by 3:30, then three hours in the gym, homework, a little family time and, occasionally, a full measure of sleep for an athlete in training. That was Monday. Tuesday included an eight-hour shift at Starbucks, then the gym, then a little sleep. Wednesday, back to school. “I promised my dad that I would be the first in our family to attend college, and I did,” says the boxer whose college education is currently on hold. He also devoured books as a teenager to improve his English.

At 18, Jose Carlos Ramirez had won more than 95 percent of his amateur fights. At 20, he learned the toughest lesson of his career about politics and corruption and the way things work in the Olympics. By all accounts, everybody who saw the fights at the 2012 London Games would attest that Jose won both of his bouts, yet came away with nothing. After defeating Rachid Azzedine in his first fight, he lost the second fight to Fazliddin Gaibnazarov of Uzbekistan in a highly controversial decision on foreign judges’ score cards. Humbled by the experience, certainly wiser, but no less determined, Jose knew one thing – it was time to turn pro. His final amateur record was 152-11 with 11 national titles and six consecutive USA gold medals, breaking Oscar De La Hoya’s all-time record.

Mentor, Manager, Mirigian

Two years before the London Summer Games, promoter Rick Mirigian was rising rapidly in a career of staging big events like Beyonce concerts and sold-out MMA fights. A risk-taker who once spent an entire student loan check to throw a party at Fresno State, Mirigian wanted nothing to do with conventional boxing nor the hard-luck kids who fill its lower ranks.

“I didn’t even want to watch, I just wasn’t interested,” Marigian says.

But, he did watch. And what he saw that day during his own MMA festival at Chukchansi Park was an epiphany.

“I wasn’t quite sure what I was seeing, but I knew it was special, and this kid Ramirez was more than special,” he says.

He spent the next few days studying all he could find about the young boxer named Jose Carlos Ramirez. Mirigian, the hard negotiator and skeptical promoter, couldn’t find any negatives.

“In my line of work everybody lies. But one thing that doesn’t lie is the numbers. I said to myself, I’m looking at something that historically and generationally just doesn’t happen.”

October 25th, 2014. Selland Arena is sold out. It’s “Fight For Water-3.” The crowd of ten thousand is raucous. An abundance of jungle theatre bounces off the walls, a Mexi-rap rant roars at incredible wattage, the room shimmers with electricity and skittering light. Boos break out as opponent David Rodela sashays to the ring. He and his people wait in a small cluster on the canvas. He dances the dance. He shadow boxes. Twitchy. He hops from foot to foot. He waits. And waits.

Suddenly the crowd roars to its feet. Elvis left the building a long time ago, but Jose Carlos Ramirez has just entered it – the effect is the same. Surrounded by his people in a Conga line from locker room to boxing ring, Ramirez stares straight ahead – he admits later that he hears none of the commotion. A gentle and generous soul, he seems out of place in this ocean of bloodlust and bravado. Except that he does belong – this is his office and he’s here to punch the time clock. Hard. The bout lasts exactly fifty-seconds.

Ten times in his thirteen fights as a pro, and many times before that as an amateur, Jose Carlos Ramirez, the kid with no nickname, has knocked out his opponent. This time it’s David Rodela of Oxnard. Jose wins the vacant NABF Junior Welterweight title.

Valley of Dusty Dreams

There is a prison nearby that provides a lot of jobs, yet the south Valley town Avenal is first and always a farm town dependent upon soils and weather, God’s grace and abundant water.

“The drought has hurt a lot of people through no fault of their own — hardworking people have lost their jobs and their livelihood.” Ramirez explains. “I’ve worked these fields, almonds and peppers and everything else. This is hard work, sure, but it’s even harder NOT to have work. This drought has ruined many, many lives. I want to help them get through these hard times, as well. They are my family, too.”

Ramirez joined the Latino Water Coalition shortly after it was formed in 2007. Co-founder Mario Santoyo says he has been a vocal supporter of water rights for the agricultural sector ever since. Kings County Supervisor Richard Valle tells the story of a Water Coalition meeting in Sacramento with top legislative leaders last year that probably would not have happened if not for Ramirez’ personal request.

“When (then) Assembly Speaker John Perez walked into the room, the first thing he said was, ‘Jose Ramirez! Can I have your autograph?'”

In early September of 2014, as he was leaving to work out with well-known trainer Freddie Roach in Los Angeles for the October 25 fight, he stopped by Children’s Hospital for a quick visit. Spokeswoman Zara Arboleda says it was to be a low profile visit, cameras and reporters okay, but “no big deal.”

“So they showed up. They were only going to stay 30 minutes to an hour max. And so we go into the first room. Here’s this little boy, a Leukemia patient.

“Jose starts talking, a little awkward at first, a few minutes go by and they keep talking. Then a few minutes more and all of a sudden, they are laughing and joking around. Next thing you know it’s like 15 minutes later, and I tell them well, we’ve gotta go to the next room. ‘Well,’ Jose says, ‘I’m not finished.” His 30-minute visit with sick kids at Valley Childrens’ Hospital lasted close to four hours!

“As he was leaving, he dropped off 1,500 tickets for his Fight For Water-3 to be given specifically to hospital staff and their families,” Arboleda said.

“He’s just like that,” Valle says. “For a couple of years now he’s jumped in with both feet to help out with my Operation Gobble at Thanksgiving.”

Valle and his supporters handed out over 225 turkeys to needy families in 2013 and well over 550 last November.

“I just asked Jose to show up and help hand out the turkeys, that’s all,” Valle says. “So, I got there a couple of hours early to set up, and here he comes around the corner completely unexpected, with a caravan of five pickup trucks filled with everything else for Thanksgiving dinner. I mean bread, and veggies, and potatoes, dressing, canned goods, drinks, cranberries, pumpkin pies, all of it. He went out and bought all of that stuff with his own money. Five pickup trucks!”

Native Talent and Hard Work

“It was the largest and most comprehensive deal ever given to an amateur boxer turning pro,” Rick Mirigian explains. On November 14, 2012, after a protracted bidding war between Oscar De La Hoya’s Golden Boy Productions and Bob Arum’s Top Rank, Ramirez signed with Top Rank.

“No one in boxing thought we’d be able to produce this deal – no one.” Explains Mirigian, “It allows a brand-new fighter, Jose, to essentially co-promote his own fights in the Central Valley twice a year for five years. Unheard of.”

“It was the best business decision, that’s all,” Says Ramirez, whose favorite boxer of all time remains Oscar De La Hoya.

Mirigian made certain that Ramirez quickly became one of the most-endorsed boxers in the history of the sport. The young boxer is well-paid to lend his name to several dozen well-known companies such as Granville Homes, McDonalds, Nike, Beats by Dre, Wonderful Pistachios, Discover, Aqua Hydrate, 2XU, 9FIVE, Dodge, Pepsi, Card City, Tachi Palace Hotel and Casino and many others.

Mirigian and Ramirez immediately set out to live up to the Top Rank contract. On November 9, 2013 at the Golden Eagle Arena in Lemoore, in “Fight For Water-1,” Ramirez knocked out Erick Hernandez at 47-seconds into the first round. “We sold out the arena, 3,600 tickets,” Marigian said, “That fight alone set a Univision Television network record for attendance, revenue and sponsors.”

Next, on May 17, 2014, “Fight For Water-2,” before a crowd of 6,100 at Selland Arena, Ramirez knocked out Jesus Selig with a devastating left hook to the ribs in the second round.

Then, with that already mentioned sellout crowd of 10,000 in attendance at Selland Arena on October 25, 2014, Ramirez won his first professional championship, the NABF Junior Welterweight title. He knocked out David Rodela 50 seconds after the fight began.

“This just doesn’t happen,” Mirigian says, “the biggest names in boxing don’t draw 10,000 people to a local arena, but Jose does, and the boxing world knows it. We could sell out a larger venue, but Bill Overfelt at Selland Arena has been very good to us, so we stay.”

There will always be dispute over who is the greatest boxer of all time. Public sentiment might favor Muhammed Ali. Or Joe Louis. Or Jack Johnson. Insiders and experts fondly recall Rocky Marciano, who remains the only heavyweight champion ever to retired undefeated. Many consider Sugar Ray Robinson to be the greatest pound-for-pound boxer of all-time. The point is, someone new is always coming up through the ranks – someone younger, stronger, faster, smarter. In this generation, in the welterweight division, Jose Carlos Ramirez could be that guy.

He’s training right now at the famous Wild Card Gym in Los Angeles alongside Manny Pacquiao, who will fight Floyd Mayweather, Jr. on May 2nd in perhaps the biggest prize fight in five years. Jose often spars with Pacquiao in preparation for his own bout, “Fight For Water-4,” May 9th at Selland Arena.

In no other sport is there such a brutal, sustained, savage, and desperate man-to-man struggle for dominance. The same limbic fight-or-flight machinery of our distant ancestors’ brains is at work in the boxing ring today.

Blood is necessary, of course, and showers of sweat. Cunning and skill play into it. And pain. Involuntary shrieks when a violent hook breaks a rib. Throbbing agony while throwing dozens of haymakers with a broken knuckle or thumb or wrist. Eyes grotesquely swollen to tiny slits. Faces bruised, battered and broken. A mouth made mush and headaches from hell. And always the palpable fear of looking the fool – humiliation at the hands of a better man.

There is a prize for those who survive this mayhem. Jose Ramirez has won a taste of it and it’s sweet, indeed. Like cold, clear snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada Range on an unbearably hot summer day in an endless field of peppers.

He fights to win that cool drink of water. To share it with his family. To share it with his Valley.

[ABTM id=22]