Central California’s Water Woes

By Bud Elliott

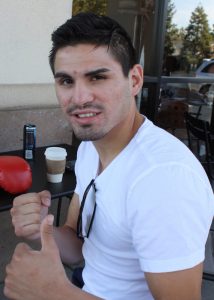

On a white hot August afternoon, farm kids gather in the cool glare of an overhead lamp at King’s Boxing Club in Avenal. They come for the boxing lessons and a cold drink of water and to escape from the fields as did Jose Ramirez, their role model and mentor.

Now considered a genuine contender for the Light Welterweight boxing championship, the strapping 22-year old Ramirez is undefeated in twelve professional fights. On October 25, at a sold-out Selland Arena, he won the vacant North American Boxing Federation junior welterweight title, just fifty seconds into the first round, by stunning David Rodela with a flurry of left jabs and a laser-guided left hook. He named it “Fight for Water-3.”

“My dad came here to work the fields at 16; we’ve always worked in ag.” Ramirez says. “This is a part of me. This is who I am, and when I see my friends and families suffering, losing their jobs because of the drought, I want to help.”

The charismatic young fighter has become a symbol for the underdogs in the water wars, which have raged in California for more than 100 years.

“Boxing has brought me to the table. I have to continue to be the voice of all those people, through the Latino Water Coalition, and through my fights,” Ramirez says.

Late in September, just days before the municipal water supply would have run out, Jose’s town got some good news for a change: The Bureau of Reclamation agreed to supply Avenal with an emergency allotment of 450 acre-feet of water from the San Luis Reservoir’s meager supply – enough to get them, and the nearby Avenal State Prison, through until next March when annual allocations are announced. (photo #8997)

Avenal, which has practiced strict water conservation measures since 1935, is wholly dependent upon water from the state and federally-managed Central Valley Project.

However, this year surface water allocations from federal water reservoirs were squeezed to a trickle by four years of what many now recognize as the worst drought in California history.

“Just like heaven. Ever’body wants a little piece of lan’. I read plenty of books out here. Nobody never gets to heaven, and nobody gets no land.” – John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

Eighty-five years ago, the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression pushed many of these families out of Oklahoma and Texas to what they saw as the Promised Land — the San Joaquin Valley. Today, the mega-drought threatens to shove many of them back to where they came from.

“There are three things that come together to make this valley utterly unique — the finest agricultural district in the world,” explains dairy farmer Mark Watte of Tulare. “First, length of growing season and predictability of weather. Second, generally good soils throughout. And, third, water. Historically, we’ve had all three in abundance and that allowed us to become the world’s top producer of food and fiber in many, many categories.” (photo #9076)

Watte’s face darkens slightly as he continues, “In many ways, this really is the Garden of Eden, but political and environmental over-reach are about to throw us off the land. I truly believe that some people want this rich farming heritage to simply go away.”

“I think that’s genuinely true for some of the smaller fringe – groups,” says Professor Jay Lund, Director of the Center for Watershed Science at UC Davis. “And rhetorically true for some of the larger fringe groups because they usually have enough smart people to understand that you’re not really going to get rid of agriculture down there, but the rhetoric is good for fundraising.”

BARREN FIELDS AND BITTER HARVESTS

Kansas Avenue from Avenal to Tulare is an unbroken vista of dead, dry fields of tumbleweeds and wild oats cut through by empty canals and the rusted pumps of long played out wells. Once there were onions and broccoli, cotton and corn, and hundreds of other crops flowing to the horizon. Now, the drip puddles are parched and crackled in the universal symbol of desolation.

This is a drought with no memory, no conscience, no scruples and no mercy. Tens of thousands of jobs have simply evaporated into the hazy summer sky. A half million acres of the nation’s most productive farmland have been taken out of production. Green trees, lawns, and landscapes have been repainted an awful shade of brown in thousands of neighborhoods and public areas. The state’s economy suffers a $2.2-billion dollar hit each year the drought drags on.

Every Spring, the federal Climate Prediction Center tries to ascertain the intentions of El Niño, that fickle ghost which sometimes warms an equatorial portion of the Pacific Ocean sufficiently to influence the jet stream to carry early and substantial rains to California and the West. This year the “little boy” appeared early, then ducked behind a cloud and hasn’t been seen since.

Climatologists do not agree on the exact description of our current dilemma — some say it’s a “hundred-year drought,” others call it a “thirty-year drought,” and on December 5th, researchers the University of Minnesota and Woods Hole Oceanographic Instutition who study tree rings announced that the drought is the worst in 1,200 years. Dr. David Zoldoske, Director of the International Center for Water Technology at Fresno State University simply says, “We’re entering year four of a ten-year drought. And when people ask, ‘(ten years?) how do you know?’ I reply, Because nobody knows that we’re not.”

RACE TO THE BOTTOM

Fifty miles east of Avenal, the rural towns of Farmersville, Munson, Springville, Lindsay, Terra Bella and East Porterville are out of water. Their wells have run dry because of heavy pumping from thousands of agricultural, residential, and municipal wells scattered along the western slope of the Sierra Nevada Range. So dire is the shortage of clean drinking water that the Red Cross was called several times last summer to deliver emergency supplies. One week before Thanksgiving, at a cost of $30,000 per month, the Tulare County Office of Emergency Services set up portable showers in an East Porterville church parking lot. For the first time in months, residents could take hot showers.

“It’s because surface water deliveries from the normal water-holding reservoirs have been cut off this year by the feds,” says Ron Jacobsma, who runs the sprawling Friant Water Authority, supplier of water to 1,500 municipal and agricultural customers. “For the first time in its 65-year history, Friant water users received exactly no water this year even though they paid for it. People are frustrated and angrier than I’ve ever seen. They’re ready to fight.”

On October 24, the 15,000 Friant Water Users filed suit against the state Water Resources Control Board, claiming it had illegally diverted a huge pool of water from Millerton Lake to serve environmental programs such as wildlife refuges, leaving cities and towns and farms with nothing. Illegal, they say, because the state bullied its way to the front of the line, leap-frogging over senior water rights owners who have valid claims dating back to the mid-1800s.

In the rich citrus belt stretching along the foothills of Fresno, Tulare, and Kern counties, some farmers are not farming for profit or even to produce a quality crop these days — they are simply hoping to keep their trees alive with well water. “Because if these trees die – some of them are 80-years old and still producing – if they die, it will cost the farmer about $60,000 to replant just one acre of trees. There are tens of thousands of acres at risk,” Jacobsma adds.

Three hundred domestic wells petered out last summer in East Porterville, leaving nearly a thousand people without drinking water.

“[Well drilling companies] wanted $10,000 to deepen our well,” says Debra Madrigal, whose 50-foot well — operating since the house was built in 1935 — went dry in June. “It might just as well have been a million dollars — we don’t have it.”

What she does have is an enterprising husband who rigged up the neighborhood’s first tank-in-a-tree. It’s a 250-gallon fiberglass contraption snuggled into the arms of a sturdy oak tree 25-feet off the ground.

“It looks complicated, but it’s really simple. My husband brings home water from a relative in Tulare in a 250-gallon tank in his truck. We pump it up to the tree tank. Gravity then feeds water back into the well where the pump pushes it into the house for washing, bathing, toilets, and so on.”

Madrigal says they buy bottled water for drinking and cooking, but for everything else, “it works great.”

WEST SIDE WASTE

“Everything you see along here that’s green is being grown with well water.”

On the west side of the San Joaquin Valley from Los Banos to the Kettleman Hills, rancher Shawn Coburn points to occasional patches of green in an ocean of burnt umber. Hundreds of thousands of acres of highly-productive farmland lie dead and dry and deserted, taken out of production for lack of surface water. Some — many people, actually — call it a “man-made” drought, an unintended consequence of water-hungry environmental programs.

Dr. Peter Gleick, President of the Pacific Institute in Oakland disagrees. “The shortage of water for agriculture is not because of environmental protection; you hear that from some of the lobbying groups in Sacramento. I think that’s misleading. The amount of water that has been returned to the environment is very, very small compared to the amount of water that some people argue ought to be returned to the environment.”

“If they had run the pumps one week longer we’d have gotten an actual water allocation this year,” counters Coburn, who’s fallowed more than half of his 3,500 acres in three counties on the West Side. He’s referring to the gigantic state and federal pumps near Tracy, part of the Central Valley Project, which are intended to move water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta into the California Aqueduct (photo #8992) for delivery in the southern two-thirds of the state.

But increasingly in recent years, these pumps have been restricted by court rulings favoring fish habitat and river restoration environmental projects. Only three times in the last 20 years have Westlands Water District customers, like Coburn, received their full contractual allotment of water. “Instead, bureaucrats stubbornly refused to run the pumps even though the regulations would have allowed it. As a result, in late March (of 2013), another 300,000 acre-feet of water just flowed right out to the ocean, of no beneficial use to anyone. Incredible.” Coburn says.

In December, 2012 and January, 2013, another 812,000 acre-feet of water went straight to the ocean for the same reason.

These days, Shawn Coburn and countless other farmers spend most of their waking hours frantically looking for water.

“Back in May, a friend of mine was completely out of water and was desperate to keep his nut trees alive, Coburn said. “I helped him find 400 acre-feet available in Southern California. We out-bid several buyers, including the City of Santa Barbara, and paid $2,200 per acre-foot for water that would have been considered expensive at $200 an acre foot five years ago.” (An acre-foot of water is 325,851 gallons, The City of Fresno uses about 153,000 acre-feet of water per year. Millerton Lake holds 550,000 acre-feet. Deep wells pulled 1.5-million acre-feet of water from beneath the San Joaquin Valley in 2014.)

Coburn operates dozens of water wells to drip-irrigate his tomatoes, wine grapes, almonds and pomegranates. He installed a new 1,200-foot well last summer that cost $500,000. Neighbors are drilling down 2,000 feet to find marginal quality water at a million dollars a hole. The expense of lifting that deep water to the surface is staggering — brutish 450-to-650 horsepower diesel or electric motors running full-out, costing thousands of dollars a day to operate.

Well drilling outfits are booked solid for the next 24 months. If you want a well drilled or re-worked anywhere in the Central Valley, plan on a crew showing up in January of 2017. Maybe.

Almond rancher Juan Guadian knows only too well that not all water is created equal. For his 150-acre grove near Manning Avenue & I-5 (and I-5) – all highlyefficient drip irrigated – he received virtually no surface water this year.

“We had to pump to keep the trees alive,” Guadian says. “But well water is no good for these trees.” He points to damaged, unhealthy leaves on his almond trees, a sure sign of salt poisoning. “Too much boron, too much salts — it fries them. These trees are very sensitive, they want cool mountain water.”

His harvest was smaller this year and of inferior quality. “If these trees die, I die,” he says. The buds are already on the trees – they will make next year’s crop. They are puny and sparse and obviously stressed.

Nearby, at the sprawling 30,000-acre Harris Farms and Harris Ranch, the water crisis has upset and re-arranged the entire operation. One example: Harris farms simply did not plant 3,000-acres of lettuce this year. Lettuce thrives on surface water but struggles on well water. Last year Harris Farms supplied lettuce for the entire “In ‘N Out” burger chain.

This year, zero.

“Nobody’s gonna plant anything right now,” says Shawn Coburn, “They’d be a fool to plant now.”

“The solution to our problem is more than rain.” — Mark Twain

How did we get into this mess?

“It’s really simple,” says Aubrey Bettencourt of the California Water Alliance. “The California water system was built four decades ago when the population was about 20-million. Today it’s nearly 40-million, yet the system of storage and conveyance has not been expanded at all. “We desperately need additional storage capacity. We need a better way to get water from Northern California to Southern California without harming the environmentally delicate Delta estuary.”

Restoring the Delta ecosystem was the purpose of the Central Valley Project Improvement Act, which Congress passed in 1992. The legislation introduced a brand new, very thirsty water consumer – the environment.

“They’re first in line. They get nearly half of available water right off the top, every year,” says Ron Jacobsma. “They’ve taken several million acre-feet of water every year for twenty years and yet the fish population hasn’t improved one bit. And the Delta ecosystem is no healthier today than it was 20 years ago.”

Farmers, municipalities, and commercial water users all blame various federal and state agencies for incompetence in managing the state’s most fragile resource. Some use a stronger word.

“Well, it is criminal,” says Karen Musson, managing partner of Gar Tootellian, Inc., one of the biggest ag consultancies in the state, “Yes, criminal in that the state and federal agencies with the power and authority to manage our water resources fairly and effectively simply haven’t done so.”

Professor Jay Lund of UC Davis agrees, up to a point, “The regulators are in a terrible position because if they try to be flexible they are always subject to being sued by one of the other sides. If you’re a regulator, a bureaucrat, just doing your job, you’re sort of stuck. The safest thing to do is not be flexible.”

“We had better start acting as though this is not an unusual event, but in fact, the new normal,” says Dr. Gleick of the Pacific Institute. “There is no longer enough water to go around to meet everybody’s demand for everything they want in California. And I think we can no longer assume that the traditional solutions are going to bail us out.”

A week before Thanksgiving, under pressure from environmentalists, Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) abruptly pulled out of what were seen as the most promising water negotiations with Republican congressional leaders in years. Both sides indicated that they were quietly nearing agreement on legislation, based on a bill authored by Congressman David Valadao which was approved last February by the House of Representatives, but held up in the Senate. It would begin addressing inequities in the Central Valley Project Improvement Act of 1992.

On the table were new water storage projects, limits on certain aspects of environmental protections in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, and removal of certain wild-and-scenic rivers protections in order to move along vital water projects.. Congressman Jim Costa was involved in those discussions all summer. “We were 95 percent in agreement,” he says, “we got very close.” He credits Senator Dianne Feinstein for working hard to address the drought, “Senator Feinstein believes that we need to have greater operational flexibility in the operation of the federal project, and Senator Boxer is not convinced that we need to move legislatively.”

According to the California Department of Food and Agriculture, farmers use about 41percent of the state’s available water, not 80 percent as is often cited by opponents, while environmental programs consume 48%. Fresno State’s Center for Irrigation Technology reports nearly identical figures: Agricultural water use 39.8 percent, Environmental programs 49.63 percent, and all others 10.57 percent. Farmers are becoming increasingly restive over this imbalance and what they view as the arrogance of the regulators and the rule makers who seem indifferent to the absurdity of diverting a million acre feet of cool, clean Northern Sierra snowmelt straight to the ocean, as farmer Shawn Coburn asserts, “To the benefit of no one, simply because at the time (Januay 2013), the Delta smelt were swimming far from the pumps and not accessible for census-taking and opinion-making.”

Now, four years into the drought, that inflexibility is viewed by many as a cruel example of federal indifference as thousands of farmers and tens of thousands of farm workers, along with millions of water users as far south as San Diego stand by and watch in dismay as fresh water flows unused into Suisun Bay and then the ocean because, by law, it could not be diverted into canals for delivery to the Central Valley and southern California.

“I think almost everybody on the agricultural side, the urban side, and the environmental side sort of sees a train wreck coming,” says UC Davis’ Jay Lund, “and they’ll always blame different people for it.”

“I believe there are flawed biological opinions,” said Congressman Jim Costa in early December. Several years ago, he and Senator Feinstein and others asked the National Academy of Science to review the biological opinions which, in effect, allow various water agencies to divert vast quantities of water for river restoration, fish protection, and other environmental uses. Costa adds, “They pointed out the flaws that existed in the biological opinions which overlooked current science. They were peer reviewed by other real scientists, not a bunch of politicians, and they found that, in fact, the biological opinions are flawed.”

Yet these biological opinions remain the legal lynchpin that holds together the entire federal water regulatory structure which is the cause of such anger and despair.

WASTE NOT, WANT NOT

It’s true. In the past, farmers wasted some water through inefficient flood irrigation and other practices, but very few are wasting it now. The fact is, farmers, the agriculture industry, and Fresno State’s Center for Irrigation Technology Incubator help promote the adoption of many water-saving innovations that are in use all over the world today — drip irrigation, low flow emitters, super efficient overhead sprayers, recycling, recovery, conservation.

Fresno State’s Dr. David Zoldoske says drip irrigation alone has reduced farm water use by 30 percent. And, “The next big thing we’re developing is sensor technology which will allow growers to micro-manage water delivery to each individual plant, tree or vine, saving even more water and energy. We look at every year as a drought year and plan accordingly.”

“People don’t realize that farmers are the original environmentalists, the genuine environmentalists,” Karen Musson says. “We are growing more food on less land using far less water than ever before.”

“The farming community has done more on water conservation than anybody else could imagine, especially in this state, especially in this Valley,” says Manuel Cunha, President of the Nisei Farmers League, and he asks, “How much more can we do? I guess it’s not to grow any crops at all and not to feed the world.”

Cunha is adamant about agriculture’s contribution to the overall health of the California economy. “2009 figures, they are higher now, but in 2009, agriculture generated $46-billion dollars, and that $46-billion, as it rolled through the economy, had an impact of $680-billion dollars! Exactly half of the state’s $1.47-trillion economy. Why would you shut off the water to such a productive enterprise?”

Others, like farmer Mark Wadde, are asking a more pointed question, “How much water have the environmental programs been asked to do without lately?”

TRICK OR TREAT?

An unintended consequence of the drought puts deficiencies in municipal water systems at center stage. The City of Fresno, dreaming of an ambitious $410-million infrastructure upgrade, held public hearings in the month of October to explain the need.

Much of the city’s water pumping and distribution system was installed during Prohibition, when clean, safe water was required for newly-planted lawns and trees in the growing city and for distilling a particularly potent brand of spirits in the tunnels and dens beneath Fresno’s Chinatown. Now those old wooden –yes, wooden! — and clay pipes are breaking down in Fresno and cities all over the state, losing millions of gallons of water to seepage, leakage, and frequent mainline breaks.

Everyone agrees on the need for the upgrade, but many object to the cost. Lawsuits have slowed the project, which will be funded, naturally, by rate hikes. Over 70,000 water meters have been installed in Fresno during the past five years, resulting in a reported 25% reduction in water use. Still, Fresnans consume far more water per capita than the statewide average.

Mother Nature caused the drought, as she always does, by withholding ample rain and snow for a longer period of time than we humans find convenient. Then again, she always relents and provides “normal” supplies of water in subsequent years.

“It is our fault and folly not to catch and store that bounty when it arrives.” says Friant’s Ron Jacobsma. “Year four of the drought will be calamitous for many sectors of the California economy, unless we get smart and lucky. We have to capture the early storms and fill up these reservoirs, because once we get into January, pumping restrictions come in and the water is lost forever, and that will be devastating.”

Fresno State’s Zoloske agrees, but sees another aspect of the crisis.

“The general consensus is that the actual amount of precipitation falling in California won’t change much in the coming years, but, due to climate change, it will arrive in the form of rain rather than snow,” he says. “That means faster runoff, not a slow, steady snow melt. And that means we must have more storage — it would be a very wise investment.”

Will the recently approved $7.3-billion water bond issue address the storage need?

“No, not at all,” says Professor Lund, “not for this issue. This is an issue of both the state and federal agencies as well as the local water districts being prepared to market water across jurisdictions under these kinds of dire circumstances.”

Exactly one week after the Friant Water Authority filed suit against the state water regulators, the first substantial storm of the season brought rain and snow to the entire state. It was late Halloween night, long after the trick-or-treaters were home in bed; a soaking, all-night rain event the likes of which had not been seen in many, many months.

“Wherever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there.” — John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

Jose Ramirez boxed again at The Cosmopolitan in Las Vegas on December 13th. Again he won (or lost) with incredibly fast and accurate head and body blows launched from his left hand arsenal. His next Fresno bout is scheduled for early in 2015. It will be designated “Fight for Water-4,” because he knows that victory in the water war will not be won by first round knockouts.

“I’m standing up for the people in the only way I can,” Ramirez says. “I fight.”

[ABTM id=22]