Up to Central Camp

I’ve lived in the San Joaquin Valley practically my whole life. The Sierra Nevada range is within easy driving distance, and, indeed, I’ve been to the mountains countless times.

But I regret to say, there are still many places up there that I’ve never been to. You see, I’m a typical “flatlander.” Mountain folks love to make fun of us. We go up for a day or two and then leave. We never get to “know” the mountains like they do.

Dad and Mom had lived in North Fork in the Madera County part of the Sierra for a time when they were first married. They often took me into the hills for camping and fishing trips when I was in my pre-teen years.

But my interests did not lie up there. When Sharon and I married and started moving around the country for jobs, it was to cities — mostly big ones. After about two decades away from the Valley, we returned to finish out our careers and retire.

And now, we live in Tesoro Viejo, which is butted right up to the Sierra foothills. It’s an easy drive up those hills, and in the past year or so, I’ve made that trip a few times.

My latest one took place this past Monday. It was a gorgeous autumn morning when I headed up to join the North Fork History Group for another trip to one of those spots I had neglected to visit.

Central Camp is about 13 miles northeast of North Fork. It’s at a much higher elevation — 5,300 feet as opposed to North Fork’s 2,800. It’s more heavily forested, and it’s now a summer getaway for about 70 individuals and families who own cabins there.

And Central Camp has history. Loads of it.

We caravaned out of North Fork toward Central Camp. Our guide was Jon Norby, whose family has owned Central Camp — all of it — since the lumber company that built it back in the 1920’s went belly-up in the early 1930’s.

We caravaned out of North Fork toward Central Camp. Our guide was Jon Norby, whose family has owned Central Camp — all of it — since the lumber company that built it back in the 1920’s went belly-up in the early 1930’s.

Central Camp is not easy to get to. The road is rough and narrow and dusty and slow. Decades ago, it had been placed right on top of the tracks that had guided the railroad in and out of Central Camp during its logging days.

My car likely could not have made it through the ruts and potholes. That’s why I hitched a ride with Norby in his pick-up. The eight-mile trip from Road 274 to Central Camp took about 90 minutes. Granted, we stopped along the way to “see the sights” — including a fine overview of Bass Lake.

Those who spend summer weekends or longer at Central Camp are dedicated. Dedicated to the beauty of the mountains, the smell of the pines and the isolation that secluded mountain living provides. A tough drive does not deter them.

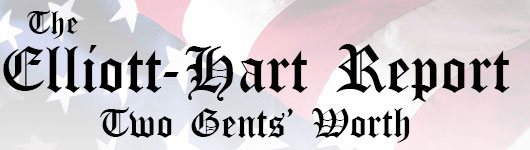

The Sugar Pine Lumber Company started building the Central Camp logging town (left) in 1922, and they spared no expense. It was said to be the finest lumber town in the United States.

The Sugar Pine Lumber Company started building the Central Camp logging town (left) in 1922, and they spared no expense. It was said to be the finest lumber town in the United States.

While Central Camp was being built, the lumber company was also putting together its sawmill more than 50 miles away. That complex was going up on nearly 600 acres of donated land in Pinedale, north of Fresno.

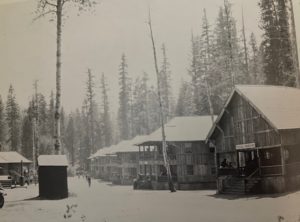

And the company — financed through two separate corporations — was also building two separate railroad connections from the sawmill to Central Camp. One was called the Minarets and Western Railway, running from the Pinedale mill to Bass Lake, and the other — the Sugar Pine Lumber Company logging railroad — ran from Bass Lake — over the dam — to Central Camp itself — a distance of about 11 miles.

The entire project took little more than one year to complete, at a cost of about $12 million. The logging town itself cost about $600,000. And what a town it was — designed to feed and house hundreds of loggers and their families from early spring until November, when it would shut down for the winter.

The entire project took little more than one year to complete, at a cost of about $12 million. The logging town itself cost about $600,000. And what a town it was — designed to feed and house hundreds of loggers and their families from early spring until November, when it would shut down for the winter.

The town had the most modern construction and features of the day. There was a school, hospital, post office, elaborate dining hall, a hotel, a boxing ring, pool hall, community store, a theater — and more. Dormitories were built for the single men, and cabins were constructed for families.

Of course, there was a machine shop, blacksmith shop, locomotive pits, construction warehouse and more.

The town was laid out on either side of a meadow, with Sand Creek running through it.

Loggers and their families could buy hearty meals at the dining hall — which seated 448 people — for 40-cents. The food was cooked in a 2,500 square foot kitchen.

Loggers and their families could buy hearty meals at the dining hall — which seated 448 people — for 40-cents. The food was cooked in a 2,500 square foot kitchen.

No one went hungry.

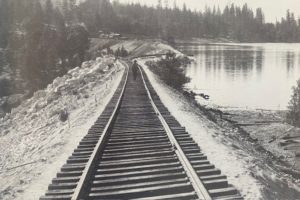

The company built more than 150 miles of railroad lines into the forest areas where logging was taking place. Dozens of trestles were constructed to get the rail cars in and out of the forest. It was quite a feat.

During the time the lumber company was operating — from 1923 through 1931 — it produced nearly 800 million board feet of lumber at its Pinedale mill. Each day, the goal was to load about three-dozen railcars with eight logs each at Central Camp — then transport them down the mountain to Pinedale. After they were unloaded, the empty cars would be brought back up to Central Camp overnight.

It’s important to distinguish the Sugar Pine operation — which used rail cars exclusively to bring logs down to Pinedale (right) where the logs could be cut into usable lumber — from three other logging operations operating in the Sierra east of Fresno at the same time.

It’s important to distinguish the Sugar Pine operation — which used rail cars exclusively to bring logs down to Pinedale (right) where the logs could be cut into usable lumber — from three other logging operations operating in the Sierra east of Fresno at the same time.

Those other operations all had lumber camps — but instead of using railroads to transport logs to their mills in Madera, Clovis and Sanger — they used flumes they had built.

And since logs were too big to float down the flumes — they had to be cut into lumber strips in the mountains and banded together before they could be floated into the Valley.

It was all amazing, and all of it went bust in the early 1930’s, courtesy of the Great Depression. No one could afford to build or buy houses, so no one had need for all the logging that had been taking place.

And thus it was that the Norby family — Jon’s grandparents — were able to buy the 640 acres of Central Camp for $3,600.

That is not a typo. They paid $3,600 for 640 acres. A square mile of land.

The family tore down almost all the buildings that had made up Central Camp’s original “town.” Today, only one structure survives — the former lumber company office. It’s been renovated several times. That’s the structure you see in the big photo above.

Once they owned Central Camp, the Norbys started selling lots to individuals who wanted to build cabins for a summer getaway. The cost back then: about $300 per lot. Now, there are about 70 of those cabins.

Once they owned Central Camp, the Norbys started selling lots to individuals who wanted to build cabins for a summer getaway. The cost back then: about $300 per lot. Now, there are about 70 of those cabins.

Most have been renovated over the decades. Some are in a “newer” part of Central Camp — above the original location. They’re a mere 60 years old or so.

The Norby family provides water to the cabins from spring to November. Three wells, with a 30,000 gallon holding tank. Because the water is turned off, most cabin owners stay away during winter, though PG&E provides power year-round. Ponderosa Telephone provides a line for Internet service.

Even with those 70 lots sold, the Norbys still own more than 600 acres of Central Camp’s nearly 640 original acres.

Even with those 70 lots sold, the Norbys still own more than 600 acres of Central Camp’s nearly 640 original acres.

It’s a fine summer getaway, indeed. Heavily wooded. Beautiful. Secluded. Quiet.

The folks who come up each summer likely know some, if not all, of Central Camp’s history.

And now — thanks to friends at the History Group — so do I.

I’m still a flatlander. But I’m trying to rise above it.