Dad’s Watch

The other day, I decided to wind up my dad’s old wristwatch. I had taken possession of it after my brother Ken passed away a few months ago. I remember seeing Dad wear it on special occasions.

That old Royal watch (15 jewels, it says on the front) sat on our bedroom bureau ever since I got it. For some reason — don’t ask me why — I wound it up, expecting nothing to happen.

After all, that watch is at least 70 and maybe 80 years old. It likely had not been wound up in decades.

To my complete astonishment, the watch worked. It kept perfect time until it ran down about 15 hours later.

And that watch started bringing back memories from a lifetime ago. Oh, so many memories — of my dad.

Let me tell you some stories…

I wish I’d had a better relationship with Dad when I was growing up. Instead — like Kevin Costner in the movie “Field of Dreams” — I saw my dad mainly as a stern, authoritarian-type guy.

Dad had worked hard all his life — starting when he was a teenager, laboring in the farm fields outside Fresno.

When he and Mom married in 1934, they moved to the mountain community of North Fork in Madera County. They clerked at the general store owned by the Franklin family. There they are, at left — so young. Their whole lives ahead of them. No way of knowing what was in store.

When he and Mom married in 1934, they moved to the mountain community of North Fork in Madera County. They clerked at the general store owned by the Franklin family. There they are, at left — so young. Their whole lives ahead of them. No way of knowing what was in store.

I wish I’d known that young man — my dad — back then. I couldn’t have, of course. But I wish I could.

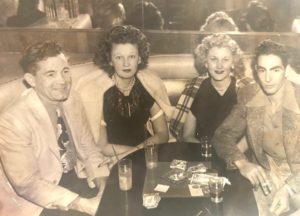

Or maybe I wish I’d known him in the 1940’s, when the photo, below right, was taken at a Fresno nightclub. My dad and mom are the two on the left. My future Aunt Irene and Uncle Ted are the two on the right. Mom looks like a deer in the headlights — but the point is, they’re young and vibrant and enjoying a night on the town.

Dad and I did not do a lot of things together — though I remember him taking me out to play my first-ever round of golf at Airways when I was perhaps 12 years old.

Dad was not big on handing out praise when I was growing up. I got great grades in school — see, I was a true nerd — but it was always Mom who looked at my report cards and laid on the accolades.

Mom took on the role of raising both Ken and me. Dad brought in the money — not a lot of it — and Mom stayed home and took care of everything else — the kids, the house, shopping — you name it.

I remember some good times with Dad. One hot summer night, he put up a tent in our backyard. We slathered on something foul-smelling to keep mosquitoes away and tried to get to sleep inside.

Maybe we did — but not until after I had heard the Santa Fe train rumbling by late that night. It was a mile away from our house, but I could hear that train clearly — a memory that has stuck with me forever

At least once, Dad and Mom and I went camping at Wishon Reservoir in the Sierra. We slept in the open, and I remember looking up at that sparkling night sky. You could seemingly see millions of stars.

I asked Dad how much closer we were to those stars than we had been, down in the Valley. I’m not sure what answer I was expecting. But when he said, “About a mile” — I was thunderstruck. How in the world could we only be a MILE closer to the stars? After all, were up at least 5,000 feet.

Yes, I was young. But I remember that night.

I also remember a remark he made to me — and the lesson he taught me — one Saturday night when I was a teenager. We were watching our black-and-white TV at home when a commercial came on for a new product — All Temperature Cheer laundry detergent. It would work even in cold water.

And — being the absolutely brilliant no-nothing I was then — I immediately spouted off something dumb like, “Why does anyone need a detergent that works in cold water?”

And Dad immediately said, “Because some people can’t afford hot water. And don’t you ever forget it.”

I never have.

We didn’t have much money — so if Dad took vacations, it would be to work around the house. Painting. Putting up a new fence. Crawling underneath the house to extend electrical wires.

He could build or fix anything. And because he did not want Ken or me to have to use our hands to make a living — as he had — Dad never taught us the skills he had. He worked on cars for a living at Crocket Brothers in downtown Fresno, but he never taught Ken or me how to fix them — or anything else.

Once, I heard, his co-workers at Crocket asked him why Ken and I weren’t working there during summer breaks from school. Someone asked Dad: “Are they too good to work here?” His response: “You’re damn right they are.”

From my earliest years, Dad made it clear I was going to college. Ken– 10 years older — had been the first Hart to go to college, and I would be the second.

Ken had graduated from Fresno State. But Dad wanted me to go to UC Berkeley and become a lawyer.

My legal interest centered around watching “Perry Mason” on TV each week. Nothing more.

So I followed Ken’s footsteps and went to Fresno State.

And then — after floundering around on campus for a year or so — I decided to go into journalism. Dad was not enthusiastic. TV or radio news was not, after all, Boalt Hall at Berkeley.

After graduation, I took a news director’s job at a radio station way, way up in northeastern California. I lasted six months before I ran out of money (I was making only $500 a month for 70 hours work a week) — so I came back to Fresno State to attend graduate school.

That’s when I got a job as a young reporter on Channel 30, met Sharon, and got married.

Dad was at our wedding, of course. But he would live only another five years before everything that had gone wrong with his body killed him at the age of 68.

He never got to see that I actually could make money in journalism.

It was only after his death that I learned more about him. About Dad, the hero.

Let me tell you some stories…

Before Dad and Mom got married, one of his early jobs was as the all-night attendant at a service station at Calaveras and Broadway in downtown Fresno.

One night, a man walked into the office and said, “Give me the money.”

Dad responded to this not-terribly-friendly conversation-opener with one word: “No.”

The would-be robber pulled out a knife and said, and not in a kind way, “This knife says you will.”

Dad pulled out a gun from under the counter and responded, quite convincingly, “This gun says I won’t.”

You cannot make this stuff up.

Then there was the time, I found out, when Dad’s elderly mother had called him from her home in Fresno’s Rooshian Town and said that Dad’s brother-in-law had struck her.

Now, understand that Dad was the protector in the Hart family. So he drove over to his mom’s place — walked in the front door — saw his brother-in-law — and, without a word, picked him up and threw him through the screen door, onto the front lawn.

Yes, through the screen door. Dad had not bothered to open it.

Then Dad strode out to the front lawn, stood over his brother-in-law, and said, I was told: “Don’t ever come back or I will harm you.” Only he did not use the term “harm.”

The brother-in-law never did come back. And his wife — one of Dad’s sisters — never talked to him again.

Then there was the night, I learned later, when Dad — who protected not only the Hart family but our entire neighborhood — heard some punks trying to break into a car parked across the street.

Dad knew what to do. While Mom called the cops, he got out of bed, picked up his shotgun, hurried outside, and hid underneath a big umbrella-type bush on the side of our house, gun pointed at the wrongdoers.

And when the cops arrived — quickly — Dad came out from underneath that bush, with his shotgun, to tell the officers what he had seen.

Imagine their surprise when this naked man stepped out from under that bush.

Yes, in Dad’s haste to “get the draw” on the scofflaws, he had neglected to put on his underwear.

I wish I’d known those stories while Dad was still alive.

I wish I’d known those stories while Dad was still alive.

But here they are — all coming back, because I wound up Dad’s wristwatch.

I have no idea when — or where — he bought it. Or how much it cost.

In fact, I know nothing about that watch — except this:

It has become priceless to me.

And I wish Dad could hear me say that.